Relational algebra

Relational algebra, an offshoot of first-order logic (and of algebra of sets), deals with a set of finitary relations (see also relation (database)) that is closed under certain operators. These operators operate on one or more relations to yield a relation. Relational algebra is a part of computer science.

Contents |

Introduction

Relational algebra received little attention outside of pure mathematics until the publication of E.F. Codd's relational model of data in 1970. Codd proposed such an algebra as a basis for database query languages. (See section Implementations.)

Relational algebra is essentially equivalent in expressive power to relational calculus (and thus first-order logic); this result is known as Codd's theorem. You must be careful to avoid a mismatch, that may arise between the two languages since negation, applied to a formula of the calculus, constructs a formula that may be true on an infinite set of possible tuples, while the difference operator of relational algebra always returns a finite result. To overcome these difficulties, Codd restricted the operands of relational algebra to finite relations only and also proposed restricted support for negation (NOT) and disjunction (OR). Analogous restrictions are found in many other logic-based computer languages. Codd defined the term relational completeness to refer to a language that is complete with respect to first-order predicate calculus apart from the restrictions he proposed. In practice the restrictions have no adverse effect on the applicability of his relational algebra for database purposes.

Primitive operations

As in any algebra, some operators are primitive and the others are derived in terms of the primitive ones. It is useful if the choice of primitive operators parallels the usual choice of primitive logical operators. Although it is well known that the usual choice in logic of AND, OR and NOT is somewhat arbitrary, Codd made a similar arbitrary choice for his algebra.

Five primitive operators of Codd's algebra are the selection, the projection, the Cartesian product (also called the cross product or cross join), the set union, the set difference. Another operator, rename was not noted by Codd, but the need for it is shown by the inventors of ISBL. These six operators are fundamental in the sense that if you omit any one of them, you will lose expressive power. Many other operators have been defined in terms of these six. Among the most important are set intersection, division, and the natural join. In fact ISBL made a compelling case for replacing the Cartesian product with the natural join, of which the Cartesian product is a degenerate case.

Altogether, the operators of relational algebra have identical expressive power to that of domain relational calculus or tuple relational calculus. However, for the reasons given in section Introduction, relational algebra is less expressive than first-order predicate calculus without function symbols. Relational algebra corresponds to a subset of first-order logic, namely Horn clauses without recursion and negation.

Set operators

Although three of the six basic operators are taken from set theory, there are additional constraints that are present in their relational algebra counterparts: For set union and set difference, the two relations involved must be union-compatible—that is, the two relations must have the same set of attributes. Because set intersection can be defined in terms of set difference, the two relations involved in set intersection must also be union-compatible.

The Cartesian product is defined differently from the one in set theory in the sense that tuples are considered to be 'shallow' for the purposes of the operation. That is, the Cartesian product of an n-tuple by an m-tuple has the 2-tuple "flattened" into an (n + m)-tuple. In set theory, the Cartesian product is a set of 2-tuples. More formally, R × S is defined as follows:

- R × S = {(r1, r2, ..., rn, s1, s2, ..., sm) | (r1, r2, ..., rn) ∈ R, (s1, s2, ..., sm) ∈ S}

Like the Cartesian product, the cardinality of the result is the product of the cardinalities of its factors, i.e., |R × S| = |R| × |S|. In addition, for the Cartesian product to be defined, the two relations involved must have disjoint headers—that is, they must not have a common attribute name.

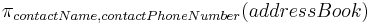

Projection (π)

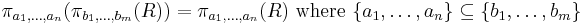

A projection is a unary operation written as  where

where  is a set of attribute names. The result of such projection is defined as the set that is obtained when all tuples in R are restricted to the set

is a set of attribute names. The result of such projection is defined as the set that is obtained when all tuples in R are restricted to the set  .

.

This specifies the specific subset of columns (attributes of each tuple) to be retrieved. To obtain the names and phone numbers from an address book, the projection might be written  . The result of that projection would be a relation which contains only the contactName and contactPhoneNumber attributes for each unique entry in addressBook.

. The result of that projection would be a relation which contains only the contactName and contactPhoneNumber attributes for each unique entry in addressBook.

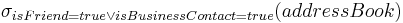

Selection (σ)

A generalized selection is a unary operation written as  where

where  is a propositional formula that consists of atoms as allowed in the normal selection and the logical operators

is a propositional formula that consists of atoms as allowed in the normal selection and the logical operators  (and),

(and),  (or) and

(or) and  (negation). This selection selects all those tuples in R for which

(negation). This selection selects all those tuples in R for which  holds.

holds.

To obtain a listing of all friends or business associates in an address book, the selection might be written as  . The result would be a relation containing every attribute of every unique record where isFriend is true or where isBusinessContact is true.

. The result would be a relation containing every attribute of every unique record where isFriend is true or where isBusinessContact is true.

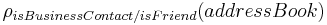

Rename (ρ)

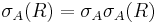

A rename is a unary operation written as  where the result is identical to R except that the b attribute in all tuples is renamed to an a attribute. This is simply used to rename the attribute of a relation or the relation itself.

where the result is identical to R except that the b attribute in all tuples is renamed to an a attribute. This is simply used to rename the attribute of a relation or the relation itself.

To rename the 'isFriend' attribute to 'isBusinessContact' in a relation,  might be used.

might be used.

Joins and join-like operators

Natural join (⋈)

Natural joins ( ) is a binary operator that is written as (R

) is a binary operator that is written as (R  S) where R and S are relations.[1] The result of the natural join is the set of all combinations of tuples in R and S that are equal on their common attribute names. For an example consider the tables Employee and Dept and their natural join:

S) where R and S are relations.[1] The result of the natural join is the set of all combinations of tuples in R and S that are equal on their common attribute names. For an example consider the tables Employee and Dept and their natural join:

|

|

|

This can also be used to define composition of relations. In category theory, the join is precisely the fiber product.

The natural join is arguably one of the most important operators since it is the relational counterpart of logical AND. Note carefully that if the same variable appears in each of two predicates that are connected by AND, then that variable stands for the same thing and both appearances must always be substituted by the same value. In particular, natural join allows the combination of relations that are associated by a foreign key. For example, in the above example a foreign key probably holds from Employee.DeptName to Dept.DeptName and then the natural join of Employee and Dept combines all employees with their departments. Note that this works because the foreign key holds between attributes with the same name. If this is not the case such as in the foreign key from Dept.manager to Employee.Name then we have to rename these columns before we take the natural join. Such a join is sometimes also referred to as an equijoin (see θ-join).

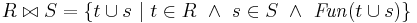

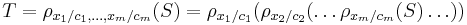

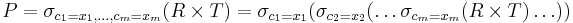

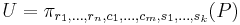

More formally the semantics of the natural join is defined as follows:

where Fun is a predicate that is true for a relation r if and only if r is a function. It is usually required that R and S must have at least one common attribute, but if this constraint is omitted, and R and S have no common attributes, then the natural join becomes exactly the Cartesian product.

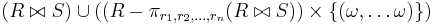

The natural join can be simulated with Codd's primitives as follows. Assume that c1,...,cm are the attribute names common to R and S, r1,...,rn are the attribute names unique to R and s1,...,sk are the attribute unique to S. Furthermore assume that the attribute names x1,...,xm are neither in R nor in S. In a first step we can now rename the common attribute names in S:

Then we take the Cartesian product and select the tuples that are to be joined:

Finally we take a projection to get rid of the renamed attributes:

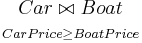

θ-join and equijoin

Consider tables Car and Boat which list models of cars and boats and their respective prices. Suppose a customer wants to buy a car and a boat, but she does not want to spend more money for the boat than for the car. The θ-join on the relation CarPrice ≥ BoatPrice produces a table with all the possible options. If you are using a condition where the attributes are equal the like Price the condition may be specified as Price=Price or alternatively (Price) itself.

|

|

|

If we want to combine tuples from two relations where the combination condition is not simply the equality of shared attributes then it is convenient to have a more general form of join operator, which is the θ-join (or theta-join). The θ-join is a binary operator that is written as  or

or  where a and b are attribute names, θ is a binary relation in the set {<, ≤, =, >, ≥}, v is a value constant, and R and S are relations. The result of this operation consists of all combinations of tuples in R and S that satisfy the relation θ. The result of the θ-join is defined only if the headers of S and R are disjoint, that is, do not contain a common attribute.

where a and b are attribute names, θ is a binary relation in the set {<, ≤, =, >, ≥}, v is a value constant, and R and S are relations. The result of this operation consists of all combinations of tuples in R and S that satisfy the relation θ. The result of the θ-join is defined only if the headers of S and R are disjoint, that is, do not contain a common attribute.

The simulation of this operation in the fundamental operations is therefore as follows:

- R

φ S = σφ(R × S)

φ S = σφ(R × S)

In case the operator θ is the equality operator (=) then this join is also called an equijoin.

Note, however, that a computer language that supports the natural join and rename operators does not need θ-join as well, as this can be achieved by selection from the result of a natural join (which degenerates to Cartesian product when there are no shared attributes).

Semijoin (⋉)(⋊)

The left semijoin is joining similar to the natural join and written as R  S where R and S are relations.[2] The result of this semijoin is the set of all tuples in R for which there is a tuple in S that is equal on their common attribute names. For an example consider the tables Employee and Dept and their semi join:

S where R and S are relations.[2] The result of this semijoin is the set of all tuples in R for which there is a tuple in S that is equal on their common attribute names. For an example consider the tables Employee and Dept and their semi join:

|

|

|

More formally the semantics of the semijoin is defined as follows:

- R

S = { t : t

S = { t : t  R, s

R, s  S, Fun (t

S, Fun (t  s) }

s) }

where Fun(r) is as in the definition of natural join.

The semijoin can be simulated using the natural join as follows. If a1, ..., an are the attribute names of R, then

- R

S =

S =  a1,..,an(R

a1,..,an(R  S).

S).

Since we can simulate the natural join with the basic operators it follows that this also holds for the semijoin.

Antijoin (▷)

The antijoin, written as R  S where R and S are relations, is similar to the natural join, but the result of an antijoin is only those tuples in R for which there is no tuple in S that is equal on their common attribute names. [3]

S where R and S are relations, is similar to the natural join, but the result of an antijoin is only those tuples in R for which there is no tuple in S that is equal on their common attribute names. [3]

For an example consider the tables Employee and Dept and their antijoin:

|

|

|

The antijoin is formally defined as follows:

- R

S = { t : t

S = { t : t  R

R

s

s  S : Fun (t

S : Fun (t  s) }

s) }

or

- R

S = { t : t

S = { t : t  R, there is no tuple s of S that satisfies Fun (t

R, there is no tuple s of S that satisfies Fun (t  s) }

s) }

where Fun(r) is as in the definition of natural join.

The antijoin can also be defined as the complement of the semijoin, as follows:

- R

S = R − R

S = R − R  S

S

Given this, the antijoin is sometimes called the anti-semijoin, and the antijoin operator is sometimes written as semijoin symbol with a bar above it, instead of  .

.

Division (÷)

The division is a binary operation that is written as R ÷ S. The result consists of the restrictions of tuples in R to the attribute names unique to R, i.e., in the header of R but not in the header of S, for which it holds that all their combinations with tuples in S are present in R. For an example see the tables Completed, DBProject and their division:

|

|

|

If DBProject contains all the tasks of the Database project, then the result of the division above contains exactly the students who have completed both of the tasks in the Database project.

More formally the semantics of the division is defined as follows:

- R ÷ S = { t[a1,...,an] : t

R

R

s

s  S ( (t[a1,...,an]

S ( (t[a1,...,an]  s)

s)  R) }

R) }

where {a1,...,an} is the set of attribute names unique to R and t[a1,...,an] is the restriction of t to this set. It is usually required that the attribute names in the header of S are a subset of those of R because otherwise the result of the operation will always be empty.

The simulation of the division with the basic operations is as follows. We assume that a1,...,an are the attribute names unique to R and b1,...,bm are the attribute names of S. In the first step we project R on its unique attribute names and construct all combinations with tuples in S:

- T := πa1,...,an(R) × S

In the prior example, T would represent a table such that every Student (because Student is the unique key / attribute of the Completed table) is combined with every given Task. So Eugene, for instance, would have two rows, Eugene -> Database1 and Eugene -> Database2 in T.

In the next step we subtract R from this relation:

- U := T − R

Note that in U we have the possible combinations that "could have" been in R, but weren't. So if we now take the projection on the attribute names unique to R then we have the restrictions of the tuples in R for which not all combinations with tuples in S were present in R:

- V := πa1,...,an(U)

So what remains to be done is take the projection of R on its unique attribute names and subtract those in V:

- W := πa1,...,an(R) − V

Outer joins

Whereas the result of a join (or inner join) consists of tuples formed by combining matching tuples in the two operands, an outer join contains those tuples and additionally some tuples formed by extending an unmatched tuple in one of the operands by "fill" values for each of the attributes of the other operand.

The operators defined in this section assume the existence of a null value, ω, which we do not define, to be used for the fill values. It should not be assumed that this is the NULL defined for the database language SQL, nor should it be assumed that ω is a mark rather than a value, nor should it be assumed that the controversial three-valued logic is introduced by it.

Three outer join operators are defined: left outer join, right outer join, and full outer join. (The word "outer" is sometimes omitted.)

Left outer join (⟕)

The left outer join is written as R ⟕ S where R and S are relations.[4] The result of the left outer join is the set of all combinations of tuples in R and S that are equal on their common attribute names, in addition (loosely speaking) to tuples in R that have no matching tuples in S.

For an example consider the tables Employee and Dept and their left outer join:

|

|

|

In the resulting relation, tuples in S which have no common values in common attribute names with tuples in R take a null value, ω.

Since there are no tuples in Dept with a DeptName of Finance or Executive, ωs occur in the resulting relation where tuples in DeptName have tuples of Finance or Executive.

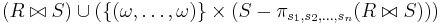

Let r1, r2, ..., rn be the attributes of the relation R and let {(ω, ..., ω)} be the singleton relation on the attributes that are unique to the relation S (those that are not attributes of R). Then the left outer join can be described in terms of the natural join (and hence using basic operators) as follows:

Right outer join (⟖)

The right outer join behaves almost identically to the left outer join, but the roles of the tables are switched.

The right outer join of relations R and S is written as R ⟖ S.[5] The result of the right outer join is the set of all combinations of tuples in R and S that are equal on their common attribute names, in addition to tuples in S that have no matching tuples in R.

For example consider the tables Employee and Dept and their right outer join:

|

|

|

In the resulting relation, tuples in R which have no common values in common attribute names with tuples in S take a null value, ω.

Since there are no tuples in Employee with a DeptName of Production, ωs occur in the Name attribute of the resulting relation where tuples in DeptName had tuples of Production.

Let s1, s2, ..., sn be the attributes of the relation S and let {(ω, ..., ω)} be the singleton relation on the attributes that are unique to the relation R (those that are not attributes of S). Then, as with the left outer join, the right outer join can be simulated using the natural join as follows:

Full outer join (⟗)

The outer join or full outer join in effect combines the results of the left and right outer joins.

The full outer join is written as R ⟗ S where R and S are relations.[6] The result of the full outer join is the set of all combinations of tuples in R and S that are equal on their common attribute names, in addition to tuples in S that have no matching tuples in R and tuples in R that have no matching tuples in S in their common attribute names.

For an example consider the tables Employee and Dept and their full outer join:

|

|

|

In the resulting relation, tuples in R which have no common values in common attribute names with tuples in S take a null value, ω. Tuples in S which have no common values in common attribute names with tuples in R also take a null value, ω.

The full outer join can be simulated using the left and right outer joins (and hence the natural join and set union) as follows:

- R ⟗ S = (R ⟕ S)

(R ⟖ S)

(R ⟖ S)

Operations for domain computations

Aggregation

There are five aggregate functions that are included with most databases. These operations are Sum, Count, Average, Maximum and Minimum. In relational algebra the aggregation operation over a schema (A1, A2, ... An) is written as follows:

G1, G2, ..., Gm g f1(A1'), f2(A2'), ..., fk(Ak') (r)

where each Aj', 1 ≤ j ≤ k, is one of the original attributes Ai, 1 ≤ i ≤ n.

The attributes preceding the g are grouping attributes, which function like a "group by" clause in SQL. Then there are an arbitrary number of aggregation functions applied to individual attributes. The operation is applied to an arbitrary relation r. The grouping attributes are optional, and if they are not supplied, the aggregation functions are applied across the entire relation to which the operation is applied.

Let's assume that we have a table named Account with three columns, namely Account_Number, Branch_Name and Balance. We wish to find the maximum balance of each branch. This is accomplished by Branch_NameGMax(Balance)(Account). To find the highest balance of all accounts regardless of branch, we could simply write GMax(Balance)(Account).

The extend operation

The extend operation is used for computed attributes. For example, if you have an attribute that contains the price of some item and another attribute that contains the quantity of that item, you can form a computed attribute: EXTEND (price * quantity) AS Total_Price.

Limitation of relational algebra

Although relational algebra seems powerful enough for most practical purposes, there are some simple and natural operators on relations which cannot be expressed by relational algebra. One of them is transitive closure of a binary relation. Given a domain D, let binary relation R be a subset of DxD. The transitive closure R+ of R is the smallest subset of DxD containing R which satifies the following condition:

x

x  y

y  z ((x,y)

z ((x,y)  R+

R+  (y,z)

(y,z)  R+

R+  (x,z)

(x,z)  R+)

R+)

There is no relational algebra expression E(R) taking R as a variable argument which produces R+. This can be proved using the fact that, given a relational expression E for which it is claimed that E(R) = R+, where R is a variable, we can always find an instance r of R (and a corresponding domain d) such that E(r) ≠ r+.[7]

Use of algebraic properties for query optimization

Queries can be represented as a tree, where

- the internal nodes are operators,

- leaves are relations,

- subtrees are subexpressions.

Our primary goal is to transform expression trees into equivalent expression trees, where the average size of the relations yielded by subexpressions in the tree are smaller than they were before the optimization. Our secondary goal is to try to form common subexpressions within a single query, or if there are more than one queries being evaluated at the same time, in all of those queries. The rationale behind that second goal is that it is enough to compute common subexpressions once, and the results can be used in all queries that contain that subexpression.

Here we present a set of rules, that can be used in such transformations.

Selection

Rules about selection operators play the most important role in query optimization. Selection is an operator that very effectively decreases the number of rows in its operand, so if we manage to move the selections in an expression tree towards the leaves, the internal relations (yielded by subexpressions) will likely shrink.

Basic selection properties

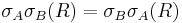

Selection is idempotent (multiple applications of the same selection have no additional effect beyond the first one), and commutative (the order selections are applied in has no effect on the eventual result).

Breaking up selections with complex conditions

A selection whose condition is a conjunction of simpler conditions is equivalent to a sequence of selections with those same individual conditions, and selection whose condition is a disjunction is equivalent to a union of selections. These identities can be used to merge selections so that fewer selections need to be evaluated, or to split them so that the component selections may be moved or optimized separately.

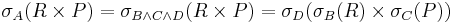

Selection and cross product

Cross product is the costliest operator to evaluate. If the input relations have N and M rows, the result will contain  rows. Therefore it is very important to do our best to decrease the size of both operands before applying the cross product operator.

rows. Therefore it is very important to do our best to decrease the size of both operands before applying the cross product operator.

This can be effectively done, if the cross product is followed by a selection operator, e.g.  (R × P). Considering the definition of join, this is the most likely case. If the cross product is not followed by a selection operator, we can try to push down a selection from higher levels of the expression tree using the other selection rules.

(R × P). Considering the definition of join, this is the most likely case. If the cross product is not followed by a selection operator, we can try to push down a selection from higher levels of the expression tree using the other selection rules.

In the above case we break up condition A into conditions B, C and D using the split rules about complex selection conditions, so that A = B  C

C  D and B only contains attributes from R, C contains attributes only from P and D contains the part of A that contains attributes from both R and P. Note, that B, C or D are possibly empty. Then the following holds:

D and B only contains attributes from R, C contains attributes only from P and D contains the part of A that contains attributes from both R and P. Note, that B, C or D are possibly empty. Then the following holds:

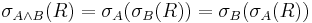

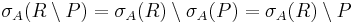

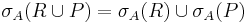

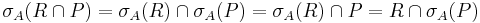

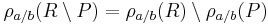

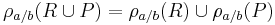

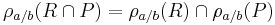

Selection and set operators

Selection is distributive over the setminus, intersection, and union operators. The following three rules are used to push selection below set operations in the expression tree. Note, that in the setminus and the intersection operators it is possible to apply the selection operator to only one of the operands after the transformation. This can make sense in cases, where one of the operands is small, and the overhead of evaluating the selection operator outweighs the benefits of using a smaller relation as an operand.

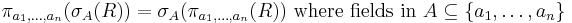

Selection and projection

Selection is associative with projection if and only if the fields referenced in the selection condition are a subset of the fields in the projection. Performing selection before projection may be useful if the operand is a cross product or join. In other cases, if the selection condition is relatively expensive to compute, moving selection outside the projection may reduce the number of tuples which must be tested (since projection may produce fewer tuples due to the elimination of duplicates resulting from elided fields).

Projection

Basic projection properties

Projection is idempotent, so that a series of (valid) projections is equivalent to the outermost projection.

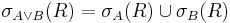

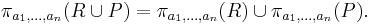

Projection and set operators

Projection is distributive over set union.

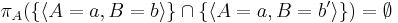

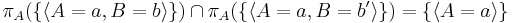

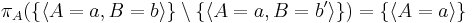

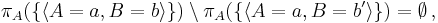

Projection does not distribute over intersection and set difference. Counterexamples are given by:

and

where b is assumed to be distinct from b'.

Rename

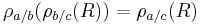

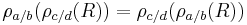

Basic rename properties

Successive renames of a variable can be collapsed into a single rename. Rename operations which have no variables in common can be arbitrarily reordered with respect to one another, which can be exploited to make successive renames adjacent so that they can be collapsed.

Rename and set operators

Rename is distributive over set difference, union, and intersection.

Implementations

The first query language to be based on Codd's algebra was ISBL, and this pioneering work has been acclaimed by many authorities as having shown the way to make Codd's idea into a useful language. Business System 12 was a short-lived industry-strength relational DBMS that followed the ISBL example.

In 1998 Chris Date and Hugh Darwen proposed a language called Tutorial D intended for use in teaching relational database theory, and its query language also draws on ISBL's ideas. Rel is an implementation of Tutorial D.

Even the query language of SQL is loosely based on a relational algebra, though the operands in SQL (tables) are not exactly relations and several useful theorems about the relational algebra do not hold in the SQL counterpart (arguably to the detriment of optimisers and/or users).

See also

- Cartesian product

- Database

- Logic of relatives

- Object role modeling

- Relation (database)

- Projection (mathematics)

- Projection (relational algebra)

- Projection (set theory)

- Relation

- Relation algebra

- Relational calculus

- Relation construction

- Relation composition

- Relation reduction

- Relational database

- Relational model

- Theory of relations

- Triadic relation

- Tutorial D

- D (data language specification)

- D4 (programming language) (an implementation of D)

References

- ^ In Unicode, the bowtie symbol is ⋈ (U+22C8).

- ^ In Unicode, the ltimes symbol is ⋉ (U+22C9). The rtimes symbol is ⋊ (U+22CA)

- ^ In Unicode, the Antijoin symbol is ▷ (U+25B7).

- ^ In Unicode, the Left outer join symbol is ⟕ (U+27D5).

- ^ In Unicode, the Right outer join symbol is ⟖ (U+27D6).

- ^ In Unicode, the Full Outer join symbol is ⟗ (U+27D7).

- ^ Aho, Alfred V.; Jeffrey D. Ullman (1979). "Universality of data retrieval languages". Proceedings of the 6th ACM SIGACT-SIGPLAN symposium on Principles of programming languages: 110–119. doi:10.1145/567752.567763. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=567763&coll=GUIDE&dl=ACM&CFID=26858249&CFTOKEN=38966071.

External links

- RAT. Software Relational Algebra Translator to SQL

- Lecture Notes: Relational Algebra – A quick tutorial to adapt SQL queries into relational algebra

- LEAP – An implementation of the relational algebra

- Relational – A graphic implementation of the relational algebra

- Query Optimization This paper is an introduction into the use of the relational algebra in optimizing queries, and includes numerous citations for more in-depth study.

- bandilab.org – neat graphical illustrations of the relational operators

- Relational Algebra System for Oracle and Microsoft SQL Server

|

||||||||||||||||||||